HISTORY 293: Dirty Wars and Democracy

Fall 2012

Instructor: Steve Volk

Class times: Tues/Thurs 9:30-10:50; King 337

Office Hours: Mondays, 2-3:00 PM; Tuesdays, 11:00-Noon; Wednesdays, 9-10:00 AM and by appointment.

Email: [email protected]; on-campus phone: x58522

"The antonym of forgetting is not remembering, it is justice," Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi

Linked Classes:

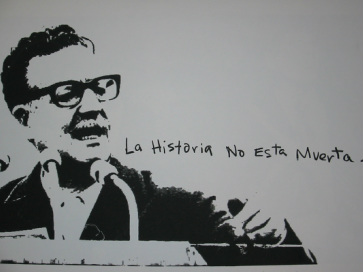

Salvador Allende (Mural on wall in Valparaiso, 2010)

LATS 293-01: Dirty Wars-LxC (Spanish) section . Wednesday, 2:30-3:30 PM. An extra discussion section in Spanish open to students in the main class. Readings and discussion in Spanish. 1 credit.

POLT 269-01: Latin American Politics Past and Present through Film . Introduction, screening, and discussion of films from the Latin American New Wave cinema, which present powerful critiques of social justice, political power, and economic conditions in the region. Focus on films from Argentina and Chile. This course is open to students co-enrolled in “Dirty Wars”. Discussions groups in Spanish or English. 1 credit.

Between 1964 and 1976, nearly all of Latin America fell under military rule, including the four countries that make up South America’s “Southern Cone”: Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, and Chile. This course will focus primarily on two of these, Chile (which took pride in its democratic past), and Argentina (where military officers leapfrogged with civilian leaders from the 1930s). The course is organized around a set of central questions: Why did these states that (at least) aspired to democracy succumb to repressive dictatorships? What were the goals of those who instituted the dictatorships, how did they organize their regimes and for what purposes, and how were these “dirty war” dictatorships different from other periods of military rule in Latin America? And, what challenges, particularly to history and memory, have these dictatorships left in their wake?

We will be examining these questions from three different perspectives: the more abstract level of the collective (the state or social order); the concrete level of the individual affected by these events (the personal or family order); and the perspective of an outsider (you) who tries to imagine what these events both felt like and meant.

Studying the “dirty wars” of the Southern Cone is neither straightforward nor easy. It requires a commitment on your part to explore difficult and unsettling questions, to absorb both selfless and highly disturbing historical narratives, and to be prepared to engage not just intellectually, but emotionally with course materials and class discussions.

We will be examining these questions from three different perspectives: the more abstract level of the collective (the state or social order); the concrete level of the individual affected by these events (the personal or family order); and the perspective of an outsider (you) who tries to imagine what these events both felt like and meant.

Studying the “dirty wars” of the Southern Cone is neither straightforward nor easy. It requires a commitment on your part to explore difficult and unsettling questions, to absorb both selfless and highly disturbing historical narratives, and to be prepared to engage not just intellectually, but emotionally with course materials and class discussions.

Course Goals and Objectives:

Content Goals:

From a social or collective perspective

Skill Development:

Content Goals:

From a social or collective perspective

- To understand why political orders abandon democratic institutions;

- To understand how authoritarian leaders and regimes think about, reflect on; and narrativize their purpose and goals;

- To understand the organization of authoritarianism;

- To understand what brought about the end of these specific authoritarian regimes;

- To understand the complex post-history of such regimes, specifically through the perspective of collective memory and the way in which the present remains responsible to and contingent on the past.

- To understand individual decision-making carried out within a state of crisis and repression, specifically how individuals understood their actions in a moment of state crisis, and the nature of individual responsibility/accountability during the periods of repression that characterized these states:

- From the perspective of those in charge of repression;

- From the perspective of those who carry out repression;

- From the perspective of those who suffered repression;

- From the perspective of “bystanders” to repression.

- To understand individual decision-making after the authoritarian state ended:

- From the perspective of those who suffered;

- From the perspective of those who participated in or benefited from the repression;

- From the perspective of those who remained “outsiders” to the events.

- To think about where we position ourselves (as observers) vis-à-vis the torturer and the tortured, the repressor and the repressed;

- To think about our responsibilities as students of history and as citizens in the world.

Skill Development:

- To develop analytic (reading) and communication (writing, discussion, and presentation) skills;

- To develop a greater capacity to work collaboratively and cooperatively;

- To learn further how to apply historical lessons to the challenges of local and global citizenship.

|

Organization of Class Although this is a fairly large class, it is designed to be discussion centered, but these will only be productive if you come prepared to discuss. That means that you must keep up with the reading assignments, and that you have watched the available videocasts before the class. I know that not everyone will watch every single video lecture in a timely fashion, but my expectation is that in any given week, most of you will – which will allow us to discuss the main questions raised that week. |

Assignments, Grading, Your Responsibilities

Your primary responsibility in this class, then, is to play an active role in it. That means that you will have done the reading, watched the videocasts, and, most importantly, thought about what it all means before class.

In terms of other projects (written and multimedia), you will have two main projects/assignments, one due in each half of the semester, and two on-going projects: reading responses and your “avatar” posts. I will provide considerably more information on all of these assignments later.

Module Assignments:

Due Tuesday, Oct. 16 at the start of class: The Exceptional State in Power. A paper or project which investigates any aspect of authoritarian rule in the Southern Cone (you can go beyond Chile and Argentina, but not beyond the Southern Cone). This can be either an individual or a joint/collaborative project (with a total of 2-3 members) and can be presented either as a traditional paper or in a different format. Please let me know by October 11 if you would like time to present your project to the class. Papers should be approximately 6-8 pages; other projects of a commensurate length.

Due Thursday, Dec. 20 at 11:00 AM: A paper or project on the post-history of authoritarian regimes on one of two themes: justice and/or memory. Papers should be approximately 6-8 pages; other projects of a commensurate length.

On-Going Assignments:

Reading Responses: You are responsible for 5 “reading responses” spaced over the course of the semester. Writing responses are, as the name implies, your response to specific assigned readings as listed in the syllabus. Writing responses are due by NOON on the day BEFORE we will be discussing the reading in class. You will get further information on how to post your responses to a Blackboard discussion board and what a good response should contain.

Avatar Project. At the beginning of the semester, you will all draw a slip of paper from a box. On it you will find a few details about a person (your avatar) you will create. These will include your birth gender, birthplace, year of birth, current location, your parents’ occupations and birthplace (if different from their current location), and their religion (if not Catholic). Over the course of the semester, through weekly diary/journal entries, you will report on the lived experience of that person during the period that we are covering in class (essentially the past 40 years). Half of you will be Argentine, the other half Chilean. You will be formed into groups of 6 (3 from each country) for the purpose of reading and commenting on each other’s posts. In the syllabus, under each week that you are writing an Avatar entry, you will see the date or date-range that you will be writing from. You will get further information on the project before you start.

Your final grade will be determined on the following basis:

The point ranges I use for grading are as follows:

A+ (99-100) B+ (87-89) C+ (77-79) D+ (67-69)

A (95-98) B (83-86) C (73-76) D (63-66)

A- (90-94) B- (80-82) C- (70-72) F (below 63)

Late papers turned in without prior permission — you must request an extension before the due date of the paper — will be reduced by one grade-step for each day that an assignment is late. For example, a paper due on Tuesday, Oct. 16 turned in on Oct. 17 will get a “B-” instead of the “B” that it merited; if it is turned in on Oct. 18, it will get a “C+”, etc.

Finally:

You may request an Incomplete in the class ONLY to complete the final paper/project. To be counted, all other work which had yet to be turned in must submitted by 4:30 PM on the last day of the Reading Period, December 17.

Plagiarism and the Honor Code:

All students must sign an “Honor Code” for all assignments. This pledge states: “I affirm that I have adhered to the Honor Code in this assignment.” For further information, see the student Honor Code which you can access via Blackboard>Lookup/Directories>Honor Code. If you have questions about what constitutes plagiarism, particularly in the context of joint or collective work, please see me or raise it in class.

Attendance, Tardiness, Class Behavior, Accommodation

I expect that you will attend the class regularly because you want to, because you understand that you can’t fully participate in your own learning if you’re not there; and because you understand that in a class of this nature you have a responsibility to your classmates to contribute. I also understand that you may have to miss an occasional class. I take attendance every day as a way to learn your names and to keep track of absences. While I don’t have a specific policy on absences (i.e., only “x” number of absences are allowed), I do reserve the right to factor excessive absence from class into your final grade.

As for coming in late, texting in class, surfing the internet, loudly slurping your morning coffee, etc., I have one central rule: be considerate to those around you and to me. If you would rather use class time to change your Facebook status, that’s your loss. But if what you do on your laptop is distracting to those around you, it’s their loss, so don’t do it.

Finally, if you have a documented disability and wish to discuss academic accommodations, please contact me as soon as possible.

Your primary responsibility in this class, then, is to play an active role in it. That means that you will have done the reading, watched the videocasts, and, most importantly, thought about what it all means before class.

In terms of other projects (written and multimedia), you will have two main projects/assignments, one due in each half of the semester, and two on-going projects: reading responses and your “avatar” posts. I will provide considerably more information on all of these assignments later.

Module Assignments:

Due Tuesday, Oct. 16 at the start of class: The Exceptional State in Power. A paper or project which investigates any aspect of authoritarian rule in the Southern Cone (you can go beyond Chile and Argentina, but not beyond the Southern Cone). This can be either an individual or a joint/collaborative project (with a total of 2-3 members) and can be presented either as a traditional paper or in a different format. Please let me know by October 11 if you would like time to present your project to the class. Papers should be approximately 6-8 pages; other projects of a commensurate length.

Due Thursday, Dec. 20 at 11:00 AM: A paper or project on the post-history of authoritarian regimes on one of two themes: justice and/or memory. Papers should be approximately 6-8 pages; other projects of a commensurate length.

On-Going Assignments:

Reading Responses: You are responsible for 5 “reading responses” spaced over the course of the semester. Writing responses are, as the name implies, your response to specific assigned readings as listed in the syllabus. Writing responses are due by NOON on the day BEFORE we will be discussing the reading in class. You will get further information on how to post your responses to a Blackboard discussion board and what a good response should contain.

Avatar Project. At the beginning of the semester, you will all draw a slip of paper from a box. On it you will find a few details about a person (your avatar) you will create. These will include your birth gender, birthplace, year of birth, current location, your parents’ occupations and birthplace (if different from their current location), and their religion (if not Catholic). Over the course of the semester, through weekly diary/journal entries, you will report on the lived experience of that person during the period that we are covering in class (essentially the past 40 years). Half of you will be Argentine, the other half Chilean. You will be formed into groups of 6 (3 from each country) for the purpose of reading and commenting on each other’s posts. In the syllabus, under each week that you are writing an Avatar entry, you will see the date or date-range that you will be writing from. You will get further information on the project before you start.

Your final grade will be determined on the following basis:

- First Paper/Project (Authoritarian States): 25%

- Second Paper/Project (Justice/Memory): 25%

- Reading Responses: 20% (total)

- Avatar Project: 30% (total)

The point ranges I use for grading are as follows:

A+ (99-100) B+ (87-89) C+ (77-79) D+ (67-69)

A (95-98) B (83-86) C (73-76) D (63-66)

A- (90-94) B- (80-82) C- (70-72) F (below 63)

Late papers turned in without prior permission — you must request an extension before the due date of the paper — will be reduced by one grade-step for each day that an assignment is late. For example, a paper due on Tuesday, Oct. 16 turned in on Oct. 17 will get a “B-” instead of the “B” that it merited; if it is turned in on Oct. 18, it will get a “C+”, etc.

Finally:

You may request an Incomplete in the class ONLY to complete the final paper/project. To be counted, all other work which had yet to be turned in must submitted by 4:30 PM on the last day of the Reading Period, December 17.

Plagiarism and the Honor Code:

All students must sign an “Honor Code” for all assignments. This pledge states: “I affirm that I have adhered to the Honor Code in this assignment.” For further information, see the student Honor Code which you can access via Blackboard>Lookup/Directories>Honor Code. If you have questions about what constitutes plagiarism, particularly in the context of joint or collective work, please see me or raise it in class.

Attendance, Tardiness, Class Behavior, Accommodation

I expect that you will attend the class regularly because you want to, because you understand that you can’t fully participate in your own learning if you’re not there; and because you understand that in a class of this nature you have a responsibility to your classmates to contribute. I also understand that you may have to miss an occasional class. I take attendance every day as a way to learn your names and to keep track of absences. While I don’t have a specific policy on absences (i.e., only “x” number of absences are allowed), I do reserve the right to factor excessive absence from class into your final grade.

As for coming in late, texting in class, surfing the internet, loudly slurping your morning coffee, etc., I have one central rule: be considerate to those around you and to me. If you would rather use class time to change your Facebook status, that’s your loss. But if what you do on your laptop is distracting to those around you, it’s their loss, so don’t do it.

Finally, if you have a documented disability and wish to discuss academic accommodations, please contact me as soon as possible.

History is not dead.

Books Recommended for Purchase [NOTE: You can buy these at the bookstore or through any on-line bookseller; one copy of each book is on reserve at the library; you can also request via OhioLink]

Ariel Dorfman, Death and the Maiden (NY: Penguin), 1994.

Marguerite Feitlowitz, A Lexicon of Terror NY: Oxford University Press), 2011 – revised and updated, with new epilogue.

Michael J. Lazzara, ed., Luz Arce and Pinochet’s Chile. Testimony in the Aftermath of State Violence (NY: Palgrave Macmillan), 2011.

Patricia Marchak, God’s Assassins. State Terrorism in Argentina in the 1970s (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press), 1999.

Lois Hecht Oppenheim, Politics in Chile: Socialism, Authoritarianism, and Market Democracy, 3rd ed. (Boulder: Westview Press), 2007.

Alicia Partnoy, The Little School: Tales of Disappearance and Survival in Argentina, 2nd ed. (Cleis Press), 1998.

Naomi Roht-Arriaza, The Pinochet Effect. Transnational Justice in the Age of Human Rights (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), 2005.

For a chronology of "Political Violence and Human Rights Movements" (1954-2002) from Elizabeth Jelin, State Repression and the Labors of Memory (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 107-133, see below.

Ariel Dorfman, Death and the Maiden (NY: Penguin), 1994.

Marguerite Feitlowitz, A Lexicon of Terror NY: Oxford University Press), 2011 – revised and updated, with new epilogue.

Michael J. Lazzara, ed., Luz Arce and Pinochet’s Chile. Testimony in the Aftermath of State Violence (NY: Palgrave Macmillan), 2011.

Patricia Marchak, God’s Assassins. State Terrorism in Argentina in the 1970s (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press), 1999.

Lois Hecht Oppenheim, Politics in Chile: Socialism, Authoritarianism, and Market Democracy, 3rd ed. (Boulder: Westview Press), 2007.

Alicia Partnoy, The Little School: Tales of Disappearance and Survival in Argentina, 2nd ed. (Cleis Press), 1998.

Naomi Roht-Arriaza, The Pinochet Effect. Transnational Justice in the Age of Human Rights (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), 2005.

For a chronology of "Political Violence and Human Rights Movements" (1954-2002) from Elizabeth Jelin, State Repression and the Labors of Memory (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 107-133, see below.

Syllabus

Sept. 4, 6: Introduction: Studying the past

Main points of discussion: Why bother studying history? What does it give us? What is the relationship between history as a subject of analysis and history as lived by real people? What is your personal responsibility to history? How will we approach it in this class?

Sept. 4: Introduction: Goals and Methods: Communities of Practice

Sept. 5: Sección en Español - Para discutir: “La Historia No Está Muerta” (la frase); ¿Es más importante (significativo) la historia en latinoamérica que en los EEUU?

Sept. 6: Why Study the Past?

Reading: Simon Romero, “Leader’s Torture in the ‘70s Stirs Ghosts in Brazil,” New York Times, August 4, 2012; Tina Rosenberg, “Editorial Observer: Chile’s Military Must Now Report to One of its Past Victims,” New York Times, May 11, 2004; BBC News, “Uruguay Elects José Mujíca as President, Polls Show,” BBC News, 30 November 2009; and, “Torture in Brazil Denied by President,” New York Times, October 21, 1970.

Burke Atkerson, "Why Study History"

REFLECTION DUE: LEARNING GOALS. Please hand in, at the beginning of class on Sept. 6, a short reflection on your personal learning goals for this course: What goals do you have for this course? What do you want to learn? Think not just about content but more broadly: skills, approaches, types of interactions. Try to be specific and detailed (not just “Chilean history”, for example). Include anything you plan to do to meet your goals (e.g. weekly objectives; time schedules, periodic meetings with the teacher, etc.). 1-2 pages.

Sept. 11, 13: Aspects of Chilean history to the 1973 coup

Four different narratives about the state, the relationship of citizens to the state, and the nature of the economy contended for dominance in the early 1970s: Revolutionary Left, Parliamentary Left, Parliamentary Right; and Authoritarian Right. Besides understanding what each represented, the central question we want to answer is what shaped the eventual outcome, a military coup.

Video Assignment: Everyone should watch the following video:

Chile: The Election of Salvador Allende (11:00)

Students who have not taken HIST 110 should watch the following three videocasts:

Chile in the Nineteenth Century (29:44);

Chile: Nitrate Mining and the Labor Movement (26:30);

Chile: The Roots of Labor and Left Militancy (22:35)

Background Reading Assignment:

Lois Hecht Oppenheim, Politics in Chile: Socialism, Authoritarianism, and Market Democracy, 3rd ed. (Boulder: Westview Press, 2007), Chapters 1-4 (p. 3-97).

Avatars: Pick slips and select pseudonyms

Sept. 11: The Unidad Popular and the Left

Reading: Salvador Allende, “Chile Begins Its March Toward Socialism,” in Dale Johnson, ed., The Chilean Road to Socialism

(Garden City, NJ: Anchor Books, 1973), pp. 150-166.

Sept. 12 – Sección en Español: Discurso de triunfo de Salvador Allende (5 de septiembre de 1970)

Sept. 13: The Opposition and the Right

Reading: Gwynn Thomas, “The Legacies of Patrimonial Patriarchalism,” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and

Social Science Vol. 636:1 (July 2011): 69-87.

Some audio to listen to:

|

The audio (in the left column) is of a phone conversation captured by President Richard Nixon's secret Oval Office taping system. Nixon is speaking to his press secretary, Ron Zeigler, were made on March 23, 192. Zeigler was informing Nixon of a press conference that took place after the secret International Telephone & Telegraph (ITT) documents were leaked to Jack Anderson, a journalist. One ITT document said that Nixon had given instructions to then U.S. Ambassador Edward Korry, to do "all possible short of a Dominican Republic-type action [i.e. a full military invasion, which the U.S. carried out in that country in 1965] to keep Allende from taking power." Nixon expressed his anger at Korry, saying "he just failed, the son of a bitch…. He should have kept Allende from getting in." For more, go to the National Security Archive |

||||||

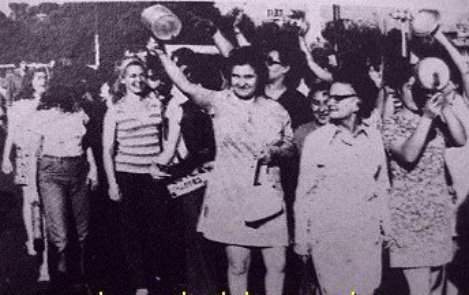

Anti-Allende "March of the Pots & Pans," December 1971

Sept. 18, 20: Argentina: Aspects of Argentine history to the 1976 coup

Central to understanding contemporary Argentine history is the phenomenon of Peronism, particularly its relationship to and impact on the labor movement and the way that Argentine leaders after Perón’s ouster in 1955 handled its challenges. Key questions to answer are how the lack of a strong institutional framework encouraged the development of a militant right and left and what position Argentine civil society occupied when the military took over.

Video Assignment: Everyone should watch the following video:

Argentina: A State in Crisis (1955-1976) (23:49)

Students who have not taken HIST 110 should watch the following two videocasts:

Argentina: The Oligarchic State (1880-1916) (23:19)

Argentina: The Rise & Fall of Peronism (36:02)

Background Reading Assignment: Patricia Marchak, God’s Assassins. State Terrorism in Argentina in the 1970s (Montreal: McGill-

Queen’s University Press, 1999), Chapters 1: Introduction (pp. 3-20).

Avatars: Hand in pseudonyms (Due on Tuesday, Sept. 18); form cross-post subgroups; setting up your blog.

Sept. 18: Perón and Peronism

Reading: Marchak, God’s Assassins, Chs. 3-5 (pp. 43-92).

Sept. 19: Sección en Español: Julio Marenales, “Breve Historia del M.L.N./Tupamaros” [OJO: es el documento casi al final de la lista]

Sept. 20: Descent to Chaos (NOTE: Barbara Sawhill of the CILC will be in class to help you set up your Avatar blogs)

Reading: Marchak, God’s Assassins, Ch. 6-8, 10 (pp. 93-145; 169-192).

Sept. 25, 27: Chile: Organizing the dictatorship

The military intervened in 1973 responding to its own sense of state crisis. The fact of its intervention only answered one question, whether the Popular Unity experiment would be allowed to continue until its mandated constitutional end in 1976. With military intervention, we now need to account for how it was that Pinochet was able to centralize power in his own circle and why he ultimately chose the governing model he did. The main questions are what were the emerging goals of Pinochet’s government and how did he organize his rule to get them.

Video Assignment:

From Repression to Reconstruction: The Political Economy of the Chilean Dictatorship (27:40)

Recommended video: Brazil: The Transition to Authoritarianism (27:00)

Avatars: First post: (Both Chile and Argentina): Late 1960s or early 1970s: Introduce yourselves. If you are still young (under 15), you may chose to have your parents introduce you.

Sept. 25: The Emergence of Pinochet and the Central Core of Power

Reading: Oppenheim, Politics in Chile, Chapters 5-6 (101-142)

Sept. 26: Sección en Español - Yom Kippur: No hay clase

Sept. 27: Pinochet in Power

Reading: Pablo Policzer, “The Rise of the DINA,” and “The DINA in Action,” Chapters 4-5 in The Rise & Fall of Repression in Chile (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009), pp. 68-111; and, Patrice McSherry, Predatory States. Operation Condor and Covert War in Latin America (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005), Chapters. 3-4 (69-138).

Click below for audio of Salvador Allende's last speech, September 11, 1973.

| salvador_allende.mp3 | |

| File Size: | 1520 kb |

| File Type: | mp3 |

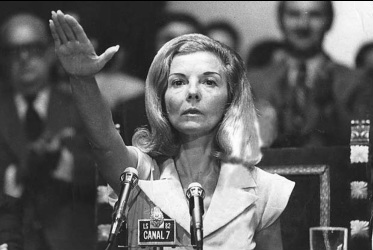

María Estela Martinez de Perón (aka, Isabelita), Perón's second wife

Oct. 2, 4: Argentina: The “dirty war”

By most accounts, when the military ousted Isabel Perón in March 1976, they had already largely completed the task of hunting down and killing/capturing most of the militant Left. The central questions for this week, then, are how we understand the goals, procedures, and ideology of the Junta leaders in Argentina. What did they want to accomplish and to what extent were their enemies real or imaginary?

Video Assignment:

Argentina: Institutionalizing the Military State - The Economic

Objectives (34:33);

Argentina: The Dirty Wars (18:51)

Avatars:

Chile: Anytime from Sept. 12, 1973 to early 1974

Argentina: Anytime from March 25, 1976 to the end of 1976

Oct. 2: The “Proceso” and the Military Perspective

Reading: Marchak, God’s Assassins, Ch. 9, 15-16 (pp. 146-168; 266-315); and Marguerite Feitlowitz, A Lexicon of Terror, rev. ed. (NY: Oxford University Press, 2011), Introduction and Chapter 1 (p. 3-71).

Oct. 3: Sección en Español - Sección en Español - Domingo Lovera Parmo, “Derechos Sociales en la Constitución del 80 (…y del 89, y del 2005),” ISCO (Universidad Diego Portales), Workingpapers ISCO-UDP, No. 3 (2009), selecciones.

Oct. 4: Confronting Violence: Visit to the AMAM

By most accounts, when the military ousted Isabel Perón in March 1976, they had already largely completed the task of hunting down and killing/capturing most of the militant Left. The central questions for this week, then, are how we understand the goals, procedures, and ideology of the Junta leaders in Argentina. What did they want to accomplish and to what extent were their enemies real or imaginary?

Video Assignment:

Argentina: Institutionalizing the Military State - The Economic

Objectives (34:33);

Argentina: The Dirty Wars (18:51)

Avatars:

Chile: Anytime from Sept. 12, 1973 to early 1974

Argentina: Anytime from March 25, 1976 to the end of 1976

Oct. 2: The “Proceso” and the Military Perspective

Reading: Marchak, God’s Assassins, Ch. 9, 15-16 (pp. 146-168; 266-315); and Marguerite Feitlowitz, A Lexicon of Terror, rev. ed. (NY: Oxford University Press, 2011), Introduction and Chapter 1 (p. 3-71).

Oct. 3: Sección en Español - Sección en Español - Domingo Lovera Parmo, “Derechos Sociales en la Constitución del 80 (…y del 89, y del 2005),” ISCO (Universidad Diego Portales), Workingpapers ISCO-UDP, No. 3 (2009), selecciones.

Oct. 4: Confronting Violence: Visit to the AMAM

Oct. 9, 11: Understanding state terror

We come to one of the most difficult parts of the course: understanding the decision to employ a policy of state terrorism and its actual implementation. We will focus in particular not just on those who authorized or carried out these policies (we have already heard from some of them), but on the real targets of state terrorism: the individual and civil society, those who might be called either “innocent bystanders” or the “silent majority” (to borrow a U.S. phrase).

Video Assignment:

The National Security State (30:32)

Avatars:

Chile: Anytime from 1975-1982

Argentina: Around or shortly after June 25, 1978 (when Argentina wins the World Cup)

Oct. 9: Moral Authority or Obedience to Authority? What we know (or don’t) from the Milgram and Zimbardo experiments

Reading: Nancy Caro Hollander, Uprooted Minds. Surviving the Politics of Terror in the Americas (NY: Routledge, 2010), chapters 4 and 5; Feitlowitz, A Lexicon of Terror, Ch. 2 (pp. 73-102), and 5 (173-223).

Oct. 10: Sección en Español - Testimonio de Alicia Partnoy [Memorias Sobre El Terrorismo De Estado, Bahía Blanca Y Punta Alta]

Oct. 11: Personal testimony

Reading: Alicia Partnoy, Little School: Tales of Disappearance and Survival in

Argentina, 2nd ed. (Cleis Press), 1998.

Optional Podcast assignment: “What Happened at Dos Erres” (This American Life, May 25, 2012), about a 1982 Guatemalan military massacred in the village of Dos Erres.

October 16 (at the start of class): First Module Paper/Project Due: Authoritarian States

We come to one of the most difficult parts of the course: understanding the decision to employ a policy of state terrorism and its actual implementation. We will focus in particular not just on those who authorized or carried out these policies (we have already heard from some of them), but on the real targets of state terrorism: the individual and civil society, those who might be called either “innocent bystanders” or the “silent majority” (to borrow a U.S. phrase).

Video Assignment:

The National Security State (30:32)

Avatars:

Chile: Anytime from 1975-1982

Argentina: Around or shortly after June 25, 1978 (when Argentina wins the World Cup)

Oct. 9: Moral Authority or Obedience to Authority? What we know (or don’t) from the Milgram and Zimbardo experiments

Reading: Nancy Caro Hollander, Uprooted Minds. Surviving the Politics of Terror in the Americas (NY: Routledge, 2010), chapters 4 and 5; Feitlowitz, A Lexicon of Terror, Ch. 2 (pp. 73-102), and 5 (173-223).

Oct. 10: Sección en Español - Testimonio de Alicia Partnoy [Memorias Sobre El Terrorismo De Estado, Bahía Blanca Y Punta Alta]

Oct. 11: Personal testimony

Reading: Alicia Partnoy, Little School: Tales of Disappearance and Survival in

Argentina, 2nd ed. (Cleis Press), 1998.

Optional Podcast assignment: “What Happened at Dos Erres” (This American Life, May 25, 2012), about a 1982 Guatemalan military massacred in the village of Dos Erres.

October 16 (at the start of class): First Module Paper/Project Due: Authoritarian States

Oct. 16, 18: It gets complicated

At some level, it is easy to condemn those who are involved in morally repugnant acts. Matters are more complicated when seen from a personal level. This week, we will explore the contradictions of the “dirty wars” when seen through the life and activities of one person, Luz Arce.

Avatars:

Chile: Anytime from 1982-1986

Argentina: Anytime from 1978-1980

Reading: Michael J. Lazzara, ed., Luz Arce and Pinochet’s Chile. Testimony in the Aftermath of State Violence (NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), Forward, pp. 1-123.

Oct. 16 and 18: Discussion of Luz Arce

At some level, it is easy to condemn those who are involved in morally repugnant acts. Matters are more complicated when seen from a personal level. This week, we will explore the contradictions of the “dirty wars” when seen through the life and activities of one person, Luz Arce.

Avatars:

Chile: Anytime from 1982-1986

Argentina: Anytime from 1978-1980

Reading: Michael J. Lazzara, ed., Luz Arce and Pinochet’s Chile. Testimony in the Aftermath of State Violence (NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), Forward, pp. 1-123.

Oct. 16 and 18: Discussion of Luz Arce

OPTIONAL: Compelling footage of one of the only times where a former prisoner confronts the person who tortured him. "People & Power" is the flagship current affairs program of Al Jazeera (English).

Oct. 17: Sección en Español - Nancy Guzmán, Romo, Confesiones de un torturador, pp. 50-83 (selecciones).

FALL BREAK

Oct. 30, Nov. 1: Contesting the dictatorship in Chile

While widespread opposition to Pinochet’s dictatorship only developed in 1982, there is evidence of opposition existing before that time. In this week we will explore two important questions that develop for those opposed to Pinochet: (1) How best to develop opposition in a police state? And, (2) should the opposition focus on Pinochet or the system that he had put in place?

Video Assignment:

Opposition to the Dictatorships: The Role of Women and Gender (37:19)

Avatars:

Chile: Anytime in 1986 to mid-1988

Argentina: Anytime from 1980 to 1982

Oct. 30: Organizing the Opposition

Reading: Oppenheim, Politics in Chile, Chapter 7 (143-166); and Cathy Lisa Schneider, “Protests in the Poblaciones,” in Shantytown Protest in Pinochet’s Chile (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995), pp. 153-189.

Oct. 31: Sección en Español - Lester R. Kurtz, “Chile: 1985-88,” International Center on Non-Violent Conflict, 2009.

Chile, La Alegria Ya Viene [YouTube]

FALL BREAK

Oct. 30, Nov. 1: Contesting the dictatorship in Chile

While widespread opposition to Pinochet’s dictatorship only developed in 1982, there is evidence of opposition existing before that time. In this week we will explore two important questions that develop for those opposed to Pinochet: (1) How best to develop opposition in a police state? And, (2) should the opposition focus on Pinochet or the system that he had put in place?

Video Assignment:

Opposition to the Dictatorships: The Role of Women and Gender (37:19)

Avatars:

Chile: Anytime in 1986 to mid-1988

Argentina: Anytime from 1980 to 1982

Oct. 30: Organizing the Opposition

Reading: Oppenheim, Politics in Chile, Chapter 7 (143-166); and Cathy Lisa Schneider, “Protests in the Poblaciones,” in Shantytown Protest in Pinochet’s Chile (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995), pp. 153-189.

Oct. 31: Sección en Español - Lester R. Kurtz, “Chile: 1985-88,” International Center on Non-Violent Conflict, 2009.

Chile, La Alegria Ya Viene [YouTube]

Nov. 1: The Plebiscite: Just Say No

Reading: Heraldo Muñoz, “To Kill Pinochet or Defeat Him with a Pencil,” in The Dictator’s Shadow. A Political Memoir (NY: Basic Books), pp. 160-208.

Nov. 6, 8: Opposition in Argentina

In looking at the nature of the opposition in Argentina, we will want to focus on two particular features: gender and the role of the Church.

Avatars:

Chile: October 6, 1988 (the day after the plebiscite)

Argentina: June 14, 1982 (Argentina surrenders to the UK in the Falklands/Malvinas War)

Reading: Heraldo Muñoz, “To Kill Pinochet or Defeat Him with a Pencil,” in The Dictator’s Shadow. A Political Memoir (NY: Basic Books), pp. 160-208.

Nov. 6, 8: Opposition in Argentina

In looking at the nature of the opposition in Argentina, we will want to focus on two particular features: gender and the role of the Church.

Avatars:

Chile: October 6, 1988 (the day after the plebiscite)

Argentina: June 14, 1982 (Argentina surrenders to the UK in the Falklands/Malvinas War)

Father Christian von Wernich, at his trial, when given a life sentence for murder, kidnapping and torture.

Nov. 6: The Role of the Church

Reading: Marchak, God’s Assassins, Chs. 13-14 (pp. 235-265); and “Argentina’s disappeared: Father Christian, the priest who did the devil’s work,” The Independent, Oct. 11, 2007.

Nov. 7: Sección en Español - Emilio Fermín Mignone, “Iglesia y dictadura La experiencia argentina,” Nueva Sociedad, 82 (Marzo-Abril 1986), pp. 121-128.

Nov. 8: The Madres de la Plaza de Mayo

Reading: Feitlowitz, A Lexicon of Terror, Ch. 3 (pp. 103-126); and Matilde Mellibovsky, Circle of Love Over Death. Testimonies of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (Willimantic, CT: Curbstone Press, 1977), pp. 81-157.

Reading: Marchak, God’s Assassins, Chs. 13-14 (pp. 235-265); and “Argentina’s disappeared: Father Christian, the priest who did the devil’s work,” The Independent, Oct. 11, 2007.

Nov. 7: Sección en Español - Emilio Fermín Mignone, “Iglesia y dictadura La experiencia argentina,” Nueva Sociedad, 82 (Marzo-Abril 1986), pp. 121-128.

Nov. 8: The Madres de la Plaza de Mayo

Reading: Feitlowitz, A Lexicon of Terror, Ch. 3 (pp. 103-126); and Matilde Mellibovsky, Circle of Love Over Death. Testimonies of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo (Willimantic, CT: Curbstone Press, 1977), pp. 81-157.

Nov. 13, 15: Transitions Out. Truth Commissions and the Search for Justice

The next two week will focus on how these countries leave their dictatorships and the struggle to address questions of justice, truth, and reconciliation in the post-dictatorial regimes. Our critical questions will ponder the issue of justice and ask both what it is and how or whether it can be achieved in post-conflict societies.

Avatars:

Chile: March 11, 1990 (the day that Patricio Aylwin is sworn in)

Argentina: Dec. 10, 1983 (the day Raul Alfonsín is sworn in)

Nov. 13: Chile’s Road Out: Truth and Reconciliation

Reading: Mary Helen Spooner, “Truth and Reconciliation,” in The General’s Slow Retreat. Chile After Pinochet (Los Angeles and Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), pp. 73-94; and Naomi Roht-Arriaza, The Pinochet Effect. Transnational Justice in the Age of Human Rights (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), Chs. 1-4 (pp. 1-117).

Nov. 14: Sección en Español - Ariel Dorfman, La muerte y la doncella (NY: Siete Cuentos Editorial), 2001.

Nov. 15: Is Justice Possible?

Reading: Ariel Dorfman, Death and the Maiden (NY: Penguin), 1994.

Nov. 20: Trials and denials in Argentina

Avatars:

Chile: March 3, 2000 (Pinochet returns after his arrest in London)

Argentina: Dec. 29, 1990 (Carlos Menem pardons junta members)

Nov. 20: Justice Denied?: Local and International Actors

The next two week will focus on how these countries leave their dictatorships and the struggle to address questions of justice, truth, and reconciliation in the post-dictatorial regimes. Our critical questions will ponder the issue of justice and ask both what it is and how or whether it can be achieved in post-conflict societies.

Avatars:

Chile: March 11, 1990 (the day that Patricio Aylwin is sworn in)

Argentina: Dec. 10, 1983 (the day Raul Alfonsín is sworn in)

Nov. 13: Chile’s Road Out: Truth and Reconciliation

Reading: Mary Helen Spooner, “Truth and Reconciliation,” in The General’s Slow Retreat. Chile After Pinochet (Los Angeles and Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), pp. 73-94; and Naomi Roht-Arriaza, The Pinochet Effect. Transnational Justice in the Age of Human Rights (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), Chs. 1-4 (pp. 1-117).

Nov. 14: Sección en Español - Ariel Dorfman, La muerte y la doncella (NY: Siete Cuentos Editorial), 2001.

Nov. 15: Is Justice Possible?

Reading: Ariel Dorfman, Death and the Maiden (NY: Penguin), 1994.

Nov. 20: Trials and denials in Argentina

Avatars:

Chile: March 3, 2000 (Pinochet returns after his arrest in London)

Argentina: Dec. 29, 1990 (Carlos Menem pardons junta members)

Nov. 20: Justice Denied?: Local and International Actors

"Justice and Punishment"

Reading: Margarita K. O’Donnell, “New Dirty War Judgments in Argentina: National Courts and Domestic Prosecutions of International Human Rights Violations,” New York University Law Review 84 (April 2009): 333-374.

David Usborne, “Dictator jailed in final judgment on Argentinian junta’s dirty war,” The Independent, Dec. 24, 2010.

Observatorio de Derechos Humanos, Branch and Rank of Armed Forces of Perpetrators Currently in Prison: Chile, May 2012.

Optional: Luis Roniger, “Transitional Justice and Protracted Accountability in Re-democratised Uruguay, 1985-2011” Journal of Latin American Studies 43 (2011): 693-724.

Nov. 21: Sección en Español - No Hay Clase (¡Tod@s a casa!)

David Usborne, “Dictator jailed in final judgment on Argentinian junta’s dirty war,” The Independent, Dec. 24, 2010.

Observatorio de Derechos Humanos, Branch and Rank of Armed Forces of Perpetrators Currently in Prison: Chile, May 2012.

Optional: Luis Roniger, “Transitional Justice and Protracted Accountability in Re-democratised Uruguay, 1985-2011” Journal of Latin American Studies 43 (2011): 693-724.

Nov. 21: Sección en Español - No Hay Clase (¡Tod@s a casa!)

Nov. 27, 29: Memory & history; history and memory

In the next two weeks, we explore issues of the relationship between history and memory, and attempt to answer how (or if) post-conflict societies can agree on what happened in their countries. At stake is more than the ability (or inability) to fashion new national historical narratives. Rather, the questions raised concerns what happens when societies don’t agree on their pasts and how (personal and collective) memory re-figures that past.

"The past has nothing more to teach us," Carlos Menem (President of Argentina, 1989-99; responsible for pardoning all the ex-commanders of the Argentina military juntas who had been convicted and jailed after the return to civilian rule)

Avatars:

Chile: Dec. 10, 2006 (Pinochet dies)

Argentina: April 19, 2005 (Adolfo Scilingo is found guilty)

Nov. 27: Memory and History: Understanding Collective Memory

Reading: Elizabeth Jelin, “Political Struggles for Memory,” and “History and Social Memory,” in State Repression and the Labors of Memory (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), pp. 26-45, 46-59.

Nov. 28: Sección en Español - El caso Pinochet (Patricio Guzmán, dir.) y ¿Llegó la Alegria?

Nov. 29: Memory, History, Family

Reading: Feitlowitz, A Lexicon of Terror, Ch. 6 (pp. 225-297); and, Francisco Goldman, “Children of the Dirty War: Argentina’s Stolen Orphans,” New Yorker, March 19, 2012.

Dec. 4, 6: Memory and commemoration

Avatars:

Chile and Argentina: Final reflection in voice of avatar. Look back at your life over the past 40 years.

Background reading for both classes: Katherine Hite, “Searching and the Intergenerational Transmission of Grief in Paine, Chile” and “The Globality of Art and Memory Making,” in Politics and the Art of Commemoration: Memorials to Struggle in Spain and Latin America (New York: Routledge, 2012), 63-89, 90-111.

Laurel Reuter, “The Disappeared,” in Los Desparecidos/The Disappeared (Italy: Charta – North Dakota Museum of Art, 2006), 25-35 (with photos and translation to Spanish in addition).

Dic. 5: Sección en Español - Patricia Tappatá de Valdez, “El parque de la memoria en Buenos Aires,” y/o Valdenia Brito, “El monumento para no olvidar: Tortura Nunca Mais en Recife,” los dos en Elizabeth Jelin y Victoria Langland, comps., Monumen- tos, memorials y marcas territoriales (Madrid: Siglo Veintiuno de España/Siglo Veintiuno de Argentina, 2003), pp. 97-111; 113-125.

For contemporary news of personal markings of commemoration of the Holocaust, see: Proudly Bearing Elders’ Scars, Their Skin Says ‘Never Forget’ (New York Times, Sept. 30, 2012)

Optional Listening: "Little War on the Prairie," This American Life (Nov. 23, 2012). A moment of great importance in the program comes toward the 55 minute mark, particularly when one of the narrators, Gwen Westerman, a Dakota woman who moved to

Mankato twenty years ago, is asked, "What do you want?"

Optional Viewing: James E. Young (Yale University): Lecture on Landscape of Memory: Holocaust Memorials in History

In the next two weeks, we explore issues of the relationship between history and memory, and attempt to answer how (or if) post-conflict societies can agree on what happened in their countries. At stake is more than the ability (or inability) to fashion new national historical narratives. Rather, the questions raised concerns what happens when societies don’t agree on their pasts and how (personal and collective) memory re-figures that past.

"The past has nothing more to teach us," Carlos Menem (President of Argentina, 1989-99; responsible for pardoning all the ex-commanders of the Argentina military juntas who had been convicted and jailed after the return to civilian rule)

Avatars:

Chile: Dec. 10, 2006 (Pinochet dies)

Argentina: April 19, 2005 (Adolfo Scilingo is found guilty)

Nov. 27: Memory and History: Understanding Collective Memory

Reading: Elizabeth Jelin, “Political Struggles for Memory,” and “History and Social Memory,” in State Repression and the Labors of Memory (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), pp. 26-45, 46-59.

Nov. 28: Sección en Español - El caso Pinochet (Patricio Guzmán, dir.) y ¿Llegó la Alegria?

Nov. 29: Memory, History, Family

Reading: Feitlowitz, A Lexicon of Terror, Ch. 6 (pp. 225-297); and, Francisco Goldman, “Children of the Dirty War: Argentina’s Stolen Orphans,” New Yorker, March 19, 2012.

Dec. 4, 6: Memory and commemoration

Avatars:

Chile and Argentina: Final reflection in voice of avatar. Look back at your life over the past 40 years.

Background reading for both classes: Katherine Hite, “Searching and the Intergenerational Transmission of Grief in Paine, Chile” and “The Globality of Art and Memory Making,” in Politics and the Art of Commemoration: Memorials to Struggle in Spain and Latin America (New York: Routledge, 2012), 63-89, 90-111.

Laurel Reuter, “The Disappeared,” in Los Desparecidos/The Disappeared (Italy: Charta – North Dakota Museum of Art, 2006), 25-35 (with photos and translation to Spanish in addition).

Dic. 5: Sección en Español - Patricia Tappatá de Valdez, “El parque de la memoria en Buenos Aires,” y/o Valdenia Brito, “El monumento para no olvidar: Tortura Nunca Mais en Recife,” los dos en Elizabeth Jelin y Victoria Langland, comps., Monumen- tos, memorials y marcas territoriales (Madrid: Siglo Veintiuno de España/Siglo Veintiuno de Argentina, 2003), pp. 97-111; 113-125.

For contemporary news of personal markings of commemoration of the Holocaust, see: Proudly Bearing Elders’ Scars, Their Skin Says ‘Never Forget’ (New York Times, Sept. 30, 2012)

Optional Listening: "Little War on the Prairie," This American Life (Nov. 23, 2012). A moment of great importance in the program comes toward the 55 minute mark, particularly when one of the narrators, Gwen Westerman, a Dakota woman who moved to

Mankato twenty years ago, is asked, "What do you want?"

Optional Viewing: James E. Young (Yale University): Lecture on Landscape of Memory: Holocaust Memorials in History

Dec. 11, 13: Current Conflicts and Post-Dictatorship Processes

What are the ways in which the issues that led to dictatorships, and the lack of resolution of issues coming out of the dictatorships, present problems which continue to confront these societies?

Avatars:

Chile and Argentina: Final reflection of avatar project in your own voice and in the context of your overall learning for course.

Dec. 11: Chile

Readings: Oppenheim, Politics in Chile, Chapters 8-9 (pp. 169-255); and Andrew Downie, “In Chile, Students’ Anger at Tuition Debt Fuels Protests and a National Debate,” Chronicle of Higher Education, Oct. 16, 2011.

Photo essay in The Atlantic (2011)

Dic. 12: Sección en Español - Gabriel Salazar, F. Atria y S. Grez, “Educación y Nueva Constitución: el horizonte político de los movimientos sociales en el Chile actual” (6 julio 2011).

Dec. 13: Argentina

Readings: Karen Ann Faulk, “If They Touch One of Us, They Touch All of Us: Cooperativism as a Counterlogic to Neoliberal Capitalism,” Anthropological Quarterly 81:3 (Summer 2008): 579-614.

Optional but recommended:Eilís O’Neill, "From Crisis to Cooperatives: Lessons from Argentina's Cartoneros," Free Speech Radio News (August 30, 2012). Eilís was a student in "Dirty Wars" in 2010 and now is an independent radio producer. The show is 29 minutes long.

Thursday, Dec. 20 at 11:00 AM: Second module paper/project due: Justice and/or Memory

Please note that I will not accept or read papers turned in after this time unless you have an official INCOMPLETE in the course. Please see me (and the assignment) for more information about this.

Avatars:

Chile and Argentina: Final reflection of avatar project in your own voice and in the context of your overall learning for course.

Dec. 11: Chile

Readings: Oppenheim, Politics in Chile, Chapters 8-9 (pp. 169-255); and Andrew Downie, “In Chile, Students’ Anger at Tuition Debt Fuels Protests and a National Debate,” Chronicle of Higher Education, Oct. 16, 2011.

Photo essay in The Atlantic (2011)

Dic. 12: Sección en Español - Gabriel Salazar, F. Atria y S. Grez, “Educación y Nueva Constitución: el horizonte político de los movimientos sociales en el Chile actual” (6 julio 2011).

Dec. 13: Argentina

Readings: Karen Ann Faulk, “If They Touch One of Us, They Touch All of Us: Cooperativism as a Counterlogic to Neoliberal Capitalism,” Anthropological Quarterly 81:3 (Summer 2008): 579-614.

Optional but recommended:Eilís O’Neill, "From Crisis to Cooperatives: Lessons from Argentina's Cartoneros," Free Speech Radio News (August 30, 2012). Eilís was a student in "Dirty Wars" in 2010 and now is an independent radio producer. The show is 29 minutes long.

Thursday, Dec. 20 at 11:00 AM: Second module paper/project due: Justice and/or Memory

Please note that I will not accept or read papers turned in after this time unless you have an official INCOMPLETE in the course. Please see me (and the assignment) for more information about this.